One particular disadvantage of such bins would be their inability to accept new footage once they had been created. This meant that I would have to ensure that all footage had been gathered and uploaded before information was changed for clips, or editing commenced. However, for my final project - which revolved around the creation of a music video - since filming required huge amounts of time, due to being performed as stop motion animation, I needed to gradually film parts and edit them before all recording had been completed. This resulted in me having to upload seventeen times, with each new collection of footage being placed in a new bin, resulting in the task being rather cumbersome.

Thursday, June 18, 2020

Organisation of Bins

In order to effectively utilise my footage whilst editing, I kept it all organised in bins that I altered to detail information about each piece. Such information included names, whether or not I saw usage, colour-coded labels, descriptions, media start times, media end times, and media duration times. This not only helped me to navigate through the many clips that I had stored, but also enabled me to quickly remember the content of each clip so that I could easily decide if and when I wanted to use it.

One particular disadvantage of such bins would be their inability to accept new footage once they had been created. This meant that I would have to ensure that all footage had been gathered and uploaded before information was changed for clips, or editing commenced. However, for my final project - which revolved around the creation of a music video - since filming required huge amounts of time, due to being performed as stop motion animation, I needed to gradually film parts and edit them before all recording had been completed. This resulted in me having to upload seventeen times, with each new collection of footage being placed in a new bin, resulting in the task being rather cumbersome.

One particular disadvantage of such bins would be their inability to accept new footage once they had been created. This meant that I would have to ensure that all footage had been gathered and uploaded before information was changed for clips, or editing commenced. However, for my final project - which revolved around the creation of a music video - since filming required huge amounts of time, due to being performed as stop motion animation, I needed to gradually film parts and edit them before all recording had been completed. This resulted in me having to upload seventeen times, with each new collection of footage being placed in a new bin, resulting in the task being rather cumbersome.

Friday, June 12, 2020

Evaluation of Editing Skills

One of the major aspects of this course was the concept of editing film in order to produce finalised pieces of work from many practical segments. By the time that the course came to an end, I had developed two large pieces, as well as four additional films that were purely designed to advance my practical skills.

My first and main editing assignment involved filming and editing a short film capturing the visible and audible style of the British new wave genre in cinema. In order to create my film to be as accurate to British new wave cinema as possible, I made sure to use as many possible editing techniques that are in favour of such a style. Although the footage was all filmed in colour, during the editing stage, I changed it to appear in monochrome, as it made the British new wave aesthetic even more prominent. Despite some films of the genre having been filmed in colour - such as Tom Jones (1963) and Alfie (1966) - it seemed wise to follow the colouration of the majority of British new wave instalments, many of which few people today will be familiar with. To further relate to the period of filmmaking at hand, all the shots contained within the film are long, and progress from one to another through jump cuts. Such cinematography was commonplace in this genre, as the long shots helped to mesmerise the audience, whereas the jump cuts worked to make the audience remember that they were watching films. Essentially, most films of the new wave genre, regardless of their country of origin, have a visual, static effect to them, due to the cameras used to film them being cheap and underdeveloped. Therefore, although my film was not recorded with any camera that would cause such an effect, I did apply a similar texture during the editing stage, in order to capture the same aesthetic. Through detailed research into British new wave editing techniques, and the clear organising of footage into bins, the piece proved itself to be rather commendable and honourable in regards to the subject matter.

Whilst I was planning my British new wave film, I was required to record footage that would used in four short films. For a certain day in each of four weeks, in order to improve my practical skills, I was provided four hours to film enough footage which would then be edited throughout the rest of the week, to produce a finished product. Such products would present new editing techniques that I had learnt in order to improve upon my knowledge of film development. For my first challenge, I filmed the college in a mysterious and haunting manner by not including any people, to give off the appearance of all previous occupants having suddenly vanished. Overall, since I had never used Adobe Premiere Pro before editing this video, I learnt the basic concepts of the software, such as importing, structuring, snipping, and reversing clips, as well as overlaying and fading music, all before exporting the completed video.

The second challenge involved me spending a few seconds filming four other students located in certain positions within one room. Each time that I stopped filming, the others would move to different locations or alter their poses for me to record. The camera would remain in the exact same position so that only the people within the film would represent change. In terms of editing, I layered the Nintendo Wii theme music over the footage, before cutting the length of the clips down, and structuring them so that each time that a new note began to sound, a new clip would play. Therefore, the main lesson learnt was how to match footage to music.

My third challenge was editing footage consisting of two students within a chase sequence. During the editing of this film, I learnt how to create iris shots, meaning that a black circle opens within the middle of the screen in order to begin the film, whilst another closes to end it. I also learnt how to input still images - in this case, title cards - as well as text, which was used to present the characters' speech, and narrate a part of the story. Additionally, discovering how to remove the colour from the footage helped keep the film remain true to 1920s cinema. The final technique that I gained understanding of was overlaying multiple pieces of footage, as the whole video plays with a film grain effect present.

To complete the fourth and final challenge, I needed to gather footage found online, before editing it to play in sychronisation with music. Ultimately, I would not say that I learnt anything new from this project, but at least I was highly satisfied with the outcome.

At a later point in the year, I was tasked with creating a music video for a song that did not already have one. To execute my overall ideas for the visuals, I decided to film and edit the video in a style of stop motion animation. Ultimately, the main aspect of this project was the practical work, as almost all materials used in the video were crafted and manipulated by hand. It would seem that the only editing aspects were the organising, snipping, and structuring of clips - none of which were new to me. This did, however, take an very large amount of time to execute, as most stop motion animation projects do. Also, it is important to remember that segment of the video is a general reflection of the song lyrics. Therefore, the segments had to begin and end as soon as the corresponding song verses do, which means that timing is key. Overall, my video has been edited to meet this requirement very well, due to careful resizing and placing of each frame.

My first and main editing assignment involved filming and editing a short film capturing the visible and audible style of the British new wave genre in cinema. In order to create my film to be as accurate to British new wave cinema as possible, I made sure to use as many possible editing techniques that are in favour of such a style. Although the footage was all filmed in colour, during the editing stage, I changed it to appear in monochrome, as it made the British new wave aesthetic even more prominent. Despite some films of the genre having been filmed in colour - such as Tom Jones (1963) and Alfie (1966) - it seemed wise to follow the colouration of the majority of British new wave instalments, many of which few people today will be familiar with. To further relate to the period of filmmaking at hand, all the shots contained within the film are long, and progress from one to another through jump cuts. Such cinematography was commonplace in this genre, as the long shots helped to mesmerise the audience, whereas the jump cuts worked to make the audience remember that they were watching films. Essentially, most films of the new wave genre, regardless of their country of origin, have a visual, static effect to them, due to the cameras used to film them being cheap and underdeveloped. Therefore, although my film was not recorded with any camera that would cause such an effect, I did apply a similar texture during the editing stage, in order to capture the same aesthetic. Through detailed research into British new wave editing techniques, and the clear organising of footage into bins, the piece proved itself to be rather commendable and honourable in regards to the subject matter.

Whilst I was planning my British new wave film, I was required to record footage that would used in four short films. For a certain day in each of four weeks, in order to improve my practical skills, I was provided four hours to film enough footage which would then be edited throughout the rest of the week, to produce a finished product. Such products would present new editing techniques that I had learnt in order to improve upon my knowledge of film development. For my first challenge, I filmed the college in a mysterious and haunting manner by not including any people, to give off the appearance of all previous occupants having suddenly vanished. Overall, since I had never used Adobe Premiere Pro before editing this video, I learnt the basic concepts of the software, such as importing, structuring, snipping, and reversing clips, as well as overlaying and fading music, all before exporting the completed video.

The second challenge involved me spending a few seconds filming four other students located in certain positions within one room. Each time that I stopped filming, the others would move to different locations or alter their poses for me to record. The camera would remain in the exact same position so that only the people within the film would represent change. In terms of editing, I layered the Nintendo Wii theme music over the footage, before cutting the length of the clips down, and structuring them so that each time that a new note began to sound, a new clip would play. Therefore, the main lesson learnt was how to match footage to music.

My third challenge was editing footage consisting of two students within a chase sequence. During the editing of this film, I learnt how to create iris shots, meaning that a black circle opens within the middle of the screen in order to begin the film, whilst another closes to end it. I also learnt how to input still images - in this case, title cards - as well as text, which was used to present the characters' speech, and narrate a part of the story. Additionally, discovering how to remove the colour from the footage helped keep the film remain true to 1920s cinema. The final technique that I gained understanding of was overlaying multiple pieces of footage, as the whole video plays with a film grain effect present.

To complete the fourth and final challenge, I needed to gather footage found online, before editing it to play in sychronisation with music. Ultimately, I would not say that I learnt anything new from this project, but at least I was highly satisfied with the outcome.

At a later point in the year, I was tasked with creating a music video for a song that did not already have one. To execute my overall ideas for the visuals, I decided to film and edit the video in a style of stop motion animation. Ultimately, the main aspect of this project was the practical work, as almost all materials used in the video were crafted and manipulated by hand. It would seem that the only editing aspects were the organising, snipping, and structuring of clips - none of which were new to me. This did, however, take an very large amount of time to execute, as most stop motion animation projects do. Also, it is important to remember that segment of the video is a general reflection of the song lyrics. Therefore, the segments had to begin and end as soon as the corresponding song verses do, which means that timing is key. Overall, my video has been edited to meet this requirement very well, due to careful resizing and placing of each frame.

Saturday, May 30, 2020

Evaluation of Practical Skills

Several crucial tasks of this course involved developing pieces of practical work in regards to film production. By the time that the course came to an end, I had developed four large pieces, as well as four additional films that were purely designed to advance my practical skills.

The course commenced with researching into the studies of camera and lighting features. This included multiple subjects, such as ISO, aperture, shutter speed and frame rate. Despite providing substantial amounts of detail for the explanations of such features, it took me quite some time to effectively make use of them. As I was constantly forgetting how to control each, I decided to write down the locations of them in terms of the camera. However, due to receiving different camera models each time that I was required to film, my writings did not help as much as I would have liked. Eventually, I had gained an adequate understanding of controlling the features, and so I was able to complete a total of seven experiments. My first was to present the effect of a focus pull, which had a successful result. The five that followed all revolved around testing certain ISO levels within particular environments. Four of these experiments specifically requested of me, and so although all but one appeared unsatisfying to the eye, they were all considered a success due to only following instructions. The final one, however, involved creating my own test, which turned out to be boring and ugly. My final experiment was to exhibit the effects of shutter speed on movement. Although this took a significant amount of time to complete, the product of a water fountain spraying liquid at different speeds was worth how long I spent gathering my footage.

In addition to experiments that I filmed personally in my own time, I also researched and witnessed others test three different lighting techniques known as Rembrandt, butterfly and split lighting. This helped me to increase my knowledge of professional film lighting by learning how to create certain effects, and when said effects should be used.

A major assignment of this course was to write an essay about a certain type of new wave cinema. Choosing to focus on the British genre, I spend many hours researching the history, filming techniques, and installments of the subject. Once the essay had been completed, I used the knowledge that I had gained to create my own new wave film following the styles of the three 1960s motion pictures that I had discussed in my written work. After planning to film my father working around some of the rural areas outside of my hometown, I ensured that my camera battery was fully charged, as I would not be able to provide it with more power when outside. Due to most British new wave films having been produced with very little equipment, and since cameras were often held by hand, or fixed onto cheap support stands, I was able to complete my film using nothing but a simple video camera and tripod. Additionally, most films of the era that I was trying to recreate were not lit by professional equipment, but merely by the cameras themselves and the daytime. Therefore, I took advantage of this by not using any external lighting sources to help produce the film, as the daylight provided enough brightness for the visuals to be seen efficiently, as well as relate to the style of filmmaking at hand. Unfortunately, there were a few shots that featured some sky, meaning that the very top of the frame was slightly overexposed, which was not, despite the cheap budgets and rushed filming, in keeping with British new wave cinema. In order to improve upon this flaw, I would either ensure that no sky was filmed, or alter the lighting features built into the camera.

As I was planning my British new wave film, I was required to record footage to be used in four short films. For a certain day in each of four weeks, in order to improve my practical skills, I was provided four hours to film enough footage which would then be edited throughout the rest of the week, to produce a finished product. For my first challenge, I filmed the college in a mysterious and haunting manner by not including any people, to give off the appearance of all previous occupants having suddenly vanished. Since this task was mainly performed to give me footage to edit so that I could familiarise myself with editing using Adobe Premiere Pro, I only learnt very basic practical skills from it. As an improvement, however, I would try to again record the shots captured outside, as they appear somewhat overexposed. To prevent this problem, this most reasonable option would be to set the camera so that the daylight does not appear too powerful, causing the colour to look slightly blanched.

The second challenge involved me spending a few seconds filming four other students located in certain positions within one room. Each time that I stopped filming, the others would move to different locations or alter their poses for me to record. The camera would remain in the exact same position so that only the people within the film would represent change. Overall, it would not be unreasonable to say that I did not learn anything new from this experience, as the main challenge was encountered during the editing of one-hundred and fifteen clips. Nevertheless, in terms of improvement, I would use external lighting to keep the tone consistent throughout the film, since it does alter very slightly as the film progresses.

Unfortunately, I learnt nothing from the third challenge, as I was not at all involved in the production of it. Therefore, once again, the main lessons arose from the editing section.

For the fourth and final film challenge, it was not even possible for me to learn anything practical, as my film had to consist of nothing but found footage. Regardless, this proved to be a blessing, as once I had finished the editing stage after many hours, the film turned out to be by far my favourite of all four.

Later into the year, I was tasked with creating a music video for a song that did not already have one. To somewhat simplify this task, I chose a song that consisted of many lyrics that I could mirror using materials. This, however, enlarged my challenged, rather than shrink it, as I came to the conclusion that I wanted to record this through stop motion animation: a technique that I had always adored, but never once used before. Due to this, the video took many weeks to produce, and although I eventually finished the filming and editing, it was not before the deadline. Thankfully, this did not matter, as what I had completed before proved my understanding of music video production. Unfortunately, due to not having a professional setup to film the video, certain aspects of production are rather deficient and unsatisfactory. For example, the lighting is not at all consistent throughout the video, as although the window blinds were closed constantly, the outside environment still managed to affect the saturation and colour scheme.In terms of camera positioning, what with creating a stop motion video, the device had to be kept in the exact same position for the whole of production. This requirement revealed itself to be slightly more difficult than I initially imagined. The camera had to be removed multiple times from the tripod in order for it to be charged. Usually, charging would occur between each new segment of the video, meaning that whenever the visuals changed to present something completely different, the background and main set piece of the mountain would unintentionally move position slightly, breaking contingency and visual flow. In order to improve upon my video, I would most certainly implement a professional lighting setup, and stick the tripod legs to floor, so that the general appearance stays consistent throughout, and a strong level of contingency is present. I would also hope to have a backdrop that is large enough to cover up the background room.

For my final practical commission, I was going to tasked with producing a promotional video for a real business client. However, due to the outbreak of COVID-19, causing many companies to close temporarily, this task could not be assigned, and so the unit was thankfully changed. Instead, I was required to plan for the production of a promotional video that would advertise a fake application known as DNA - the purpose of which was to enable users to access their family trees, and share information with their distant family members. I created many different pieces of work to help plan for such a video, including a mood board, storyboard, Gantt chart, voice actor script, finding of a music piece, and video release agreement. In addition, I also spent many hours researching everything highly specific that I would need to create the video that I had in mind. This entailed finding websites to hire and/or purchase such equipment and people from, as well as producing tables detailing how much everything would cost in total. Such equipment and people included camera and lighting equipment, a filming studio, catering, actors, hair and makeup artists, equipment technicians, property masters, a voice actor, an editor, a recording studio, and many different clothing props, resulting in an ultimate cost of £24370. Overall, although this did not provide me with real experience of communication between myself and a client, it did help me understand the true importance of planning and budgeting in regards to filmmaking. In my opinion, the area in which I did not improve was that of health and safety, since I did not include any of it in my planning. Therefore, including such information, as well as writing about how I ensured that all cast and crew members followed it, is most definitely the main improvement.

The course commenced with researching into the studies of camera and lighting features. This included multiple subjects, such as ISO, aperture, shutter speed and frame rate. Despite providing substantial amounts of detail for the explanations of such features, it took me quite some time to effectively make use of them. As I was constantly forgetting how to control each, I decided to write down the locations of them in terms of the camera. However, due to receiving different camera models each time that I was required to film, my writings did not help as much as I would have liked. Eventually, I had gained an adequate understanding of controlling the features, and so I was able to complete a total of seven experiments. My first was to present the effect of a focus pull, which had a successful result. The five that followed all revolved around testing certain ISO levels within particular environments. Four of these experiments specifically requested of me, and so although all but one appeared unsatisfying to the eye, they were all considered a success due to only following instructions. The final one, however, involved creating my own test, which turned out to be boring and ugly. My final experiment was to exhibit the effects of shutter speed on movement. Although this took a significant amount of time to complete, the product of a water fountain spraying liquid at different speeds was worth how long I spent gathering my footage.

In addition to experiments that I filmed personally in my own time, I also researched and witnessed others test three different lighting techniques known as Rembrandt, butterfly and split lighting. This helped me to increase my knowledge of professional film lighting by learning how to create certain effects, and when said effects should be used.

A major assignment of this course was to write an essay about a certain type of new wave cinema. Choosing to focus on the British genre, I spend many hours researching the history, filming techniques, and installments of the subject. Once the essay had been completed, I used the knowledge that I had gained to create my own new wave film following the styles of the three 1960s motion pictures that I had discussed in my written work. After planning to film my father working around some of the rural areas outside of my hometown, I ensured that my camera battery was fully charged, as I would not be able to provide it with more power when outside. Due to most British new wave films having been produced with very little equipment, and since cameras were often held by hand, or fixed onto cheap support stands, I was able to complete my film using nothing but a simple video camera and tripod. Additionally, most films of the era that I was trying to recreate were not lit by professional equipment, but merely by the cameras themselves and the daytime. Therefore, I took advantage of this by not using any external lighting sources to help produce the film, as the daylight provided enough brightness for the visuals to be seen efficiently, as well as relate to the style of filmmaking at hand. Unfortunately, there were a few shots that featured some sky, meaning that the very top of the frame was slightly overexposed, which was not, despite the cheap budgets and rushed filming, in keeping with British new wave cinema. In order to improve upon this flaw, I would either ensure that no sky was filmed, or alter the lighting features built into the camera.

As I was planning my British new wave film, I was required to record footage to be used in four short films. For a certain day in each of four weeks, in order to improve my practical skills, I was provided four hours to film enough footage which would then be edited throughout the rest of the week, to produce a finished product. For my first challenge, I filmed the college in a mysterious and haunting manner by not including any people, to give off the appearance of all previous occupants having suddenly vanished. Since this task was mainly performed to give me footage to edit so that I could familiarise myself with editing using Adobe Premiere Pro, I only learnt very basic practical skills from it. As an improvement, however, I would try to again record the shots captured outside, as they appear somewhat overexposed. To prevent this problem, this most reasonable option would be to set the camera so that the daylight does not appear too powerful, causing the colour to look slightly blanched.

The second challenge involved me spending a few seconds filming four other students located in certain positions within one room. Each time that I stopped filming, the others would move to different locations or alter their poses for me to record. The camera would remain in the exact same position so that only the people within the film would represent change. Overall, it would not be unreasonable to say that I did not learn anything new from this experience, as the main challenge was encountered during the editing of one-hundred and fifteen clips. Nevertheless, in terms of improvement, I would use external lighting to keep the tone consistent throughout the film, since it does alter very slightly as the film progresses.

Unfortunately, I learnt nothing from the third challenge, as I was not at all involved in the production of it. Therefore, once again, the main lessons arose from the editing section.

For the fourth and final film challenge, it was not even possible for me to learn anything practical, as my film had to consist of nothing but found footage. Regardless, this proved to be a blessing, as once I had finished the editing stage after many hours, the film turned out to be by far my favourite of all four.

Later into the year, I was tasked with creating a music video for a song that did not already have one. To somewhat simplify this task, I chose a song that consisted of many lyrics that I could mirror using materials. This, however, enlarged my challenged, rather than shrink it, as I came to the conclusion that I wanted to record this through stop motion animation: a technique that I had always adored, but never once used before. Due to this, the video took many weeks to produce, and although I eventually finished the filming and editing, it was not before the deadline. Thankfully, this did not matter, as what I had completed before proved my understanding of music video production. Unfortunately, due to not having a professional setup to film the video, certain aspects of production are rather deficient and unsatisfactory. For example, the lighting is not at all consistent throughout the video, as although the window blinds were closed constantly, the outside environment still managed to affect the saturation and colour scheme.In terms of camera positioning, what with creating a stop motion video, the device had to be kept in the exact same position for the whole of production. This requirement revealed itself to be slightly more difficult than I initially imagined. The camera had to be removed multiple times from the tripod in order for it to be charged. Usually, charging would occur between each new segment of the video, meaning that whenever the visuals changed to present something completely different, the background and main set piece of the mountain would unintentionally move position slightly, breaking contingency and visual flow. In order to improve upon my video, I would most certainly implement a professional lighting setup, and stick the tripod legs to floor, so that the general appearance stays consistent throughout, and a strong level of contingency is present. I would also hope to have a backdrop that is large enough to cover up the background room.

For my final practical commission, I was going to tasked with producing a promotional video for a real business client. However, due to the outbreak of COVID-19, causing many companies to close temporarily, this task could not be assigned, and so the unit was thankfully changed. Instead, I was required to plan for the production of a promotional video that would advertise a fake application known as DNA - the purpose of which was to enable users to access their family trees, and share information with their distant family members. I created many different pieces of work to help plan for such a video, including a mood board, storyboard, Gantt chart, voice actor script, finding of a music piece, and video release agreement. In addition, I also spent many hours researching everything highly specific that I would need to create the video that I had in mind. This entailed finding websites to hire and/or purchase such equipment and people from, as well as producing tables detailing how much everything would cost in total. Such equipment and people included camera and lighting equipment, a filming studio, catering, actors, hair and makeup artists, equipment technicians, property masters, a voice actor, an editor, a recording studio, and many different clothing props, resulting in an ultimate cost of £24370. Overall, although this did not provide me with real experience of communication between myself and a client, it did help me understand the true importance of planning and budgeting in regards to filmmaking. In my opinion, the area in which I did not improve was that of health and safety, since I did not include any of it in my planning. Therefore, including such information, as well as writing about how I ensured that all cast and crew members followed it, is most definitely the main improvement.

Thursday, May 28, 2020

History and Development of Film Editing

Film editing is both a creative and a technical part of the post-production process of filmmaking. The term is derived from the traditional process of working with film which increasingly involves the use of digital technology.

The film editor works with the raw footage by selecting shots and combining them into sequences which create a finished motion picture. Film editing is described as an art or skill unique to cinema, separating filmmaking from other art forms that preceded it, although there are close parallels to the editing process in other art forms such as poetry and novel writing. Film editing is often referred to as the 'invisible art' because when it is well-practiced, the viewer can become so engaged that they are not aware of the editor's work.

Early films were short films each consisting of a long, static, and locked-down shot. Motion in the shot was all that was necessary to amuse an audience, and so the first films simply showed activity such as traffic moving along a city street. There was never any story or editing. Each film ran as long as there was film in the camera.

The use of film editing to establish continuity, involving action moving from one sequence into another, is attributed to British film pioneer Robert W. Paul's Come Along, Do!, made in 1898 as one of the first films to feature more than one shot. In the first shot, an elderly couple is outside an art exhibition having lunch, before following other people inside through the door. The second shot shows what they do inside. Paul's 'Cinematograph Camera No. 1' of 1896 was the first camera to feature reverse-cranking, which allowed the same film footage to be exposed several times and thereby to create super-positions and multiple exposures. One of the very first films to use this technique, Georges Méliès's The Four Troublesome Heads from 1898, was produced with Paul's camera.

The further development of action continuity in multi-shot films continued in 1899-1900 at the Brighton School in England, where it was definitively established by George Albert Smith and James Williamson. In that year, Smith made As Seen Through a Telescope, in which the main shot shows a street scene with a young man tying the shoelace and then caressing the foot of his girlfriend, while an old man observes this through a telescope. There is then a cut to close shot of the hands on the girl's foot shown inside a black circular mask, and then a cut back to the continuation of the original scene.

Even more remarkable was James Williamson's Attack on a China Mission, made around the same time in 1900. The first shot shows the gate to the mission station from the outside being attacked and broken open by Chinese Boxer rebels, before there is a cut to the garden of the mission station where a pitched battle ensues. An armed party of British sailors arrive to defeat the Boxers and rescue a missionary's family. The film used the first 'reverse angle' cut in film history.

James Williamson concentrated on producing films taking action from one place shown in one shot to the next shown in another shot in films like Stop Thief! and Fire!, made in 1901, along with many others. He also experimented with the close-up, and made perhaps the most extreme one of all in The Big Swallow, when his character approaches the camera and appears to swallow it. Smith and Williamson of the Brighton School also pioneered the editing of the film; they tinted their work with colour, and used trick photography to enhance the narrative. By 1900, their films were extended scenes of up to five minutes long.

Other filmmakers took up all these ideas. Among these filmmakers was American Edwin S. Porter, who started making films for the Edison Company in 1901. Porter worked on a number of minor films before making Life of an American Fireman in 1903. The film was the first American film with a plot, featuring action, and even a closeup of a hand pulling a fire alarm. The film comprised a continuous narrative over seven scenes, rendered in a total of nine shots. He put a dissolve between every shot, just as Georges Méliès was already doing, and frequently had the same action repeated across the dissolves. His film, The Great Train Robbery, made in 1903, had a running time of twelve minutes, with twenty separate shots, and ten different indoor and outdoor locations. He used the cross-cutting editing method to show simultaneous action in different places.

These early film directors discovered important aspects of motion picture language: that the screen image does not need to show a complete person from head to toe, and that splicing together two shots creates in the viewer's mind a contextual relationship. These were the key discoveries that made all non-live or non live-on-videotape narrative motion pictures and television possible - that shots (in this case, whole scenes since each shot is a complete scene) can be photographed at widely different locations over periods of time (hours, days or even months) and combined into a narrative whole. For instance, The Great Train Robbery contains scenes shot on sets of a telegraph station, a railroad car interior, and a dance hall, with outdoor scenes at a railroad water tower, on a train itself, at a point along the track, and in the woods. However, in the film, when the robbers leave the telegraph station interior (set) and emerge at the water tower, the audience believes that the characters traveled immediately from one to the other. In addition, when they climb on the train in one shot and enter the baggage car (set) in the next, the audience believes the robbers to be on the same train.

At some point in 1918, Russian director Lev Kuleshov performed an experiment that proves this point. He took an old film clip of a head shot of Russian actor Ivan Mosjoukine, and intercut the shot with one of a bowl of soup, then with a child playing with a teddy bear, before with a shot of an elderly woman in a casket. When he showed the film to people they praised the actor's acting - the hunger in his face when he saw the soup, the delight in the child, and the grief when looking at the dead woman. Of course, the shot of the actor was filmed years before the other shots, and Ivan was never filmed 'seeing' any of the items. The simple act of juxtaposing the shots in a sequence made the relationship.

Before the widespread use of digital, non-linear editing systems, the initial editing of all films was done with a positive copy of the film negative called a film workprint, by physically cutting and splicing together pieces of film. Strips of footage would be hand-cut and attached together with tape, and then later in time, glue. Editors were very precise; if they made a wrong cut or needed a fresh positive print, it cost the production money and time for the lab to reprint the footage. Additionally, each reprint put the negative at risk of damage. With the invention of a splicer and threading the machine with a viewer such as a Moviola, or flatbed editor, such as Steenbeck or K-E-M (Keller-Elektro-Mechanik), the editing process quickened slightly, and cuts came out cleaner and more precise. The Moviola editing practice is non-linear, allowing the editor to make choices faster - a great advantage to editing episodic films for television which have very short timelines to complete the work. All film studios and production companies that produced films for television provided this tool for their editors. Flatbed editing machines were used for playback and refinement of cuts, particularly in feature films and films made for television, since they were less noisy and cleaner to work with. They were used extensively for documentary and drama production within the BBC's Film Department. Operated by a team of two, an editor and assistant editor, this tactile process required significant skill but allowed for editors to work extremely efficiently.

Today, most films are edited digitally (on systems such as Avid Media Composer, Final Cut Pro, and Adobe Premiere Pro) and bypass the film positive workprint altogether. In the past, the use of a film positive (not the original negative) allowed the editor to do as much experimenting as they wished, without the risk of damaging the original. With digital editing, editors can experiment just as much as before except with the footage completely transferred to a computer hard drive.

When the film workprint had been cut to a satisfactory state, it was then used to make an Edit Decision List (EDL). The negative cutter referred to this list whilst processing the negative, splitting the shots into rolls, which were then contact printed to produce the final film print or answer print. Today, production companies have the option of bypassing negative cutting altogether. With the advent of Digital Intermediate (DI), the physical negative does not necessarily need to be physically cut and spliced together; rather the negative is optically scanned into the computer/s, and a cut list is confirmed by a DI editor.

Post-production editing may be summarised by three distinct phases commonly referred to as the editor's cut, the director's cut, and the final cut.

There are several editing stages, with the editor's cut being the first. An editor's cut is normally the first pass of what the final film will be when it reaches picture lock. The film editor usually starts working while principal photography starts. Sometimes, prior to cutting, the editor and director will have seen and discussed 'dailies' (raw footage shot each day) as shooting progresses. As production schedules have shortened over the years, this co-viewing happens less often. Screening dailies give the editor a general idea of the director's intentions. Since it is the first pass, the editor's cut might be longer than the final film. The editor continues to refine the cut whilst shooting continues, and often, the entire editing process occurs for many months or sometimes for more than a year, depending on the film.

When shooting is finished, the director can then focus their full attention to collaborating with the editor in order to further refine the cut of the film. This is the time that is set aside in which the film editor's first cut is molded to fit the director's vision. In the United States, under the rules of the Directors Guild of America, directors receive a minimum of ten weeks after completion of principal photography to prepare their first cut. While collaborating on what is referred to as the 'director's cut', the director and the editor review the entire movie in great detail, for scenes and shots are reordered, removed, shortened and otherwise tweaked. Often it is discovered that there are plot holes, missing shots or even missing segments which might require new scenes to be filmed. Due to this time spent working closely and collaborating - a period that is normally far longer and more intricately detailed than the entire preceding film production - many directors and editors form a unique and artistic bond, thereby making arrangements to continue working with each other in similar ways on future projects.

Often after the director has had their chance to oversee a cut, the subsequent cuts are supervised by one or more producers, who represent the production company or movie studio. Interestingly, there have been several conflicts in the past between the director and the studio, sometimes leading to the use of the 'Alan Smithee' credit signifying when a director no longer wishes to be associated with the final release.

In motion picture terminology, a montage (from the French for 'putting together' or 'assembly') is a film editing technique. There are at least three senses of the term. In French film practice, 'montage' has its literal French meaning, and simply identifies editing. In Soviet filmmaking of the 1920s, 'montage' was a method of juxtaposing shots to derive new meaning that did not exist in either shot alone. In classical Hollywood cinema, a 'montage sequence' is a short segment in a film in which narrative information is presented in a condensed fashion.

Although film director D.W. Griffith was not part of the origins of montage, he was one of the early proponents of the power of editing - mastering cross-cutting to show the occurrence of parallel action in different locations, and codifying film grammar in other ways as well. Griffith's work was highly regarded by Lev Kuleshov and other Soviet filmmakers, greatly influencing their understanding of editing.

Kuleshov was among the very first to theorise about the relatively young medium of the cinema in the 1920s. For him, the unique essence of the cinema - that which could be duplicated in no other medium - was editing. He argued that editing a film is like constructing a building. Brick-by-brick (shot-by-shot), the building (film) is erected. His often-cited Kuleshov Experiment established that montage can lead the viewer to reach certain conclusions about the action within films. Montage works because viewers infer meaning based on context. Sergei Eisenstein was briefly a student of Kuleshov's, but the two parted ways because they had different ideas of montage. Eisenstein regarded montage as a dialectical means of creating meaning. By contrasting unrelated shots, he tried to provoke associations in the viewer, which were induced by shocks. Nevertheless, Eisenstein did not always perform his own editing, as some of his most important films developed were edited by Esfir Tobak.

A montage sequence consists of a series of short shots that are edited into a sequence to condense narrative. It is usually used to advance the story as a whole (often to suggest the passage of time), rather than to create symbolic meaning. In many cases, a song plays in the background to enhance the mood or reinforce the message being conveyed. One famous example of a montage sequence was seen in the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, depicting the start of man's first development from apes to humans. Another example that is employed in many films is the sports montage. The sports montage shows the star athlete training over a period of time, each shot having more improvement than the last. Classic examples of this include Rocky (1976) and The Karate Kid (1984).

Continuity is a term for the consistency of on-screen elements over the course of a scene or film, such as whether an actor's costume remains the same from one scene to the next, or whether a glass holds the same amount of liquid if not drunk throughout the scene. Since films are typically shot out of sequence, the script supervisor will keep a record of continuity, and provide that to the film editor for reference. The editor may try to maintain continuity of elements, or may intentionally create a discontinuous sequence for stylistic or narrative effect.

The technique of continuity editing, part of the classical Hollywood style, was developed by early European and American directors - in particular, D.W. Griffith in his films such as The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916). The classical style embraces temporal and spatial continuity as a way of advancing the narrative, using such techniques as the 180-degree rule, establishing shot, and shot reverse shot. Often, continuity editing entails finding a balance between literal continuity and perceived continuity. For instance, editors may condense action across cuts in a non-distracting way. A character walking from one place to another may 'skip' a section of floor from one side of a cut to the other, but the cut is constructed to appear continuous so as not to distract the viewer.

Early Russian filmmakers such as Lev Kuleshov further explored and theorised about editing and its ideological nature. Sergei Eisenstein developed a system of editing that was designed to be unconcerned with the overall rules of the continuity system of classical Hollywood that he called Intellectual montage.

Alternatives to traditional editing were also explored by early surrealist and Dada filmmakers such as Luis Buñuel (director of 1929's Un Chien Andalou) and René Clair (director of 1924's Entr'acte, which starred famous Dada artists Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray).

The French New Wave filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, as well as their American counterparts such as Andy Warhol and John Cassavetes also pushed the limits of continuity editing during the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s. French New Wave films and the non-narrative films of the 1960s used a carefree editing style, and did not conform to the traditional editing etiquette of Hollywood films. Just like its Dada and surrealist predecessors, French New Wave editing often drew attention to itself by its lack of continuity, its demystifying nature (often reminding the audience that they were watching a film), and its overt use of jump cuts or the insertion of material not often related to any narrative. Three of the most influential editors of French New Wave films were the women who (in combination) edited 15 of Godard's films. These were Françoise Collin, Agnès Guillemot, and Cécile Decugis.

The film editor works with the raw footage by selecting shots and combining them into sequences which create a finished motion picture. Film editing is described as an art or skill unique to cinema, separating filmmaking from other art forms that preceded it, although there are close parallels to the editing process in other art forms such as poetry and novel writing. Film editing is often referred to as the 'invisible art' because when it is well-practiced, the viewer can become so engaged that they are not aware of the editor's work.

Early films were short films each consisting of a long, static, and locked-down shot. Motion in the shot was all that was necessary to amuse an audience, and so the first films simply showed activity such as traffic moving along a city street. There was never any story or editing. Each film ran as long as there was film in the camera.

The use of film editing to establish continuity, involving action moving from one sequence into another, is attributed to British film pioneer Robert W. Paul's Come Along, Do!, made in 1898 as one of the first films to feature more than one shot. In the first shot, an elderly couple is outside an art exhibition having lunch, before following other people inside through the door. The second shot shows what they do inside. Paul's 'Cinematograph Camera No. 1' of 1896 was the first camera to feature reverse-cranking, which allowed the same film footage to be exposed several times and thereby to create super-positions and multiple exposures. One of the very first films to use this technique, Georges Méliès's The Four Troublesome Heads from 1898, was produced with Paul's camera.

The further development of action continuity in multi-shot films continued in 1899-1900 at the Brighton School in England, where it was definitively established by George Albert Smith and James Williamson. In that year, Smith made As Seen Through a Telescope, in which the main shot shows a street scene with a young man tying the shoelace and then caressing the foot of his girlfriend, while an old man observes this through a telescope. There is then a cut to close shot of the hands on the girl's foot shown inside a black circular mask, and then a cut back to the continuation of the original scene.

Even more remarkable was James Williamson's Attack on a China Mission, made around the same time in 1900. The first shot shows the gate to the mission station from the outside being attacked and broken open by Chinese Boxer rebels, before there is a cut to the garden of the mission station where a pitched battle ensues. An armed party of British sailors arrive to defeat the Boxers and rescue a missionary's family. The film used the first 'reverse angle' cut in film history.

James Williamson concentrated on producing films taking action from one place shown in one shot to the next shown in another shot in films like Stop Thief! and Fire!, made in 1901, along with many others. He also experimented with the close-up, and made perhaps the most extreme one of all in The Big Swallow, when his character approaches the camera and appears to swallow it. Smith and Williamson of the Brighton School also pioneered the editing of the film; they tinted their work with colour, and used trick photography to enhance the narrative. By 1900, their films were extended scenes of up to five minutes long.

Other filmmakers took up all these ideas. Among these filmmakers was American Edwin S. Porter, who started making films for the Edison Company in 1901. Porter worked on a number of minor films before making Life of an American Fireman in 1903. The film was the first American film with a plot, featuring action, and even a closeup of a hand pulling a fire alarm. The film comprised a continuous narrative over seven scenes, rendered in a total of nine shots. He put a dissolve between every shot, just as Georges Méliès was already doing, and frequently had the same action repeated across the dissolves. His film, The Great Train Robbery, made in 1903, had a running time of twelve minutes, with twenty separate shots, and ten different indoor and outdoor locations. He used the cross-cutting editing method to show simultaneous action in different places.

These early film directors discovered important aspects of motion picture language: that the screen image does not need to show a complete person from head to toe, and that splicing together two shots creates in the viewer's mind a contextual relationship. These were the key discoveries that made all non-live or non live-on-videotape narrative motion pictures and television possible - that shots (in this case, whole scenes since each shot is a complete scene) can be photographed at widely different locations over periods of time (hours, days or even months) and combined into a narrative whole. For instance, The Great Train Robbery contains scenes shot on sets of a telegraph station, a railroad car interior, and a dance hall, with outdoor scenes at a railroad water tower, on a train itself, at a point along the track, and in the woods. However, in the film, when the robbers leave the telegraph station interior (set) and emerge at the water tower, the audience believes that the characters traveled immediately from one to the other. In addition, when they climb on the train in one shot and enter the baggage car (set) in the next, the audience believes the robbers to be on the same train.

At some point in 1918, Russian director Lev Kuleshov performed an experiment that proves this point. He took an old film clip of a head shot of Russian actor Ivan Mosjoukine, and intercut the shot with one of a bowl of soup, then with a child playing with a teddy bear, before with a shot of an elderly woman in a casket. When he showed the film to people they praised the actor's acting - the hunger in his face when he saw the soup, the delight in the child, and the grief when looking at the dead woman. Of course, the shot of the actor was filmed years before the other shots, and Ivan was never filmed 'seeing' any of the items. The simple act of juxtaposing the shots in a sequence made the relationship.

Before the widespread use of digital, non-linear editing systems, the initial editing of all films was done with a positive copy of the film negative called a film workprint, by physically cutting and splicing together pieces of film. Strips of footage would be hand-cut and attached together with tape, and then later in time, glue. Editors were very precise; if they made a wrong cut or needed a fresh positive print, it cost the production money and time for the lab to reprint the footage. Additionally, each reprint put the negative at risk of damage. With the invention of a splicer and threading the machine with a viewer such as a Moviola, or flatbed editor, such as Steenbeck or K-E-M (Keller-Elektro-Mechanik), the editing process quickened slightly, and cuts came out cleaner and more precise. The Moviola editing practice is non-linear, allowing the editor to make choices faster - a great advantage to editing episodic films for television which have very short timelines to complete the work. All film studios and production companies that produced films for television provided this tool for their editors. Flatbed editing machines were used for playback and refinement of cuts, particularly in feature films and films made for television, since they were less noisy and cleaner to work with. They were used extensively for documentary and drama production within the BBC's Film Department. Operated by a team of two, an editor and assistant editor, this tactile process required significant skill but allowed for editors to work extremely efficiently.

Today, most films are edited digitally (on systems such as Avid Media Composer, Final Cut Pro, and Adobe Premiere Pro) and bypass the film positive workprint altogether. In the past, the use of a film positive (not the original negative) allowed the editor to do as much experimenting as they wished, without the risk of damaging the original. With digital editing, editors can experiment just as much as before except with the footage completely transferred to a computer hard drive.

When the film workprint had been cut to a satisfactory state, it was then used to make an Edit Decision List (EDL). The negative cutter referred to this list whilst processing the negative, splitting the shots into rolls, which were then contact printed to produce the final film print or answer print. Today, production companies have the option of bypassing negative cutting altogether. With the advent of Digital Intermediate (DI), the physical negative does not necessarily need to be physically cut and spliced together; rather the negative is optically scanned into the computer/s, and a cut list is confirmed by a DI editor.

Post-production editing may be summarised by three distinct phases commonly referred to as the editor's cut, the director's cut, and the final cut.

There are several editing stages, with the editor's cut being the first. An editor's cut is normally the first pass of what the final film will be when it reaches picture lock. The film editor usually starts working while principal photography starts. Sometimes, prior to cutting, the editor and director will have seen and discussed 'dailies' (raw footage shot each day) as shooting progresses. As production schedules have shortened over the years, this co-viewing happens less often. Screening dailies give the editor a general idea of the director's intentions. Since it is the first pass, the editor's cut might be longer than the final film. The editor continues to refine the cut whilst shooting continues, and often, the entire editing process occurs for many months or sometimes for more than a year, depending on the film.

When shooting is finished, the director can then focus their full attention to collaborating with the editor in order to further refine the cut of the film. This is the time that is set aside in which the film editor's first cut is molded to fit the director's vision. In the United States, under the rules of the Directors Guild of America, directors receive a minimum of ten weeks after completion of principal photography to prepare their first cut. While collaborating on what is referred to as the 'director's cut', the director and the editor review the entire movie in great detail, for scenes and shots are reordered, removed, shortened and otherwise tweaked. Often it is discovered that there are plot holes, missing shots or even missing segments which might require new scenes to be filmed. Due to this time spent working closely and collaborating - a period that is normally far longer and more intricately detailed than the entire preceding film production - many directors and editors form a unique and artistic bond, thereby making arrangements to continue working with each other in similar ways on future projects.

Often after the director has had their chance to oversee a cut, the subsequent cuts are supervised by one or more producers, who represent the production company or movie studio. Interestingly, there have been several conflicts in the past between the director and the studio, sometimes leading to the use of the 'Alan Smithee' credit signifying when a director no longer wishes to be associated with the final release.

In motion picture terminology, a montage (from the French for 'putting together' or 'assembly') is a film editing technique. There are at least three senses of the term. In French film practice, 'montage' has its literal French meaning, and simply identifies editing. In Soviet filmmaking of the 1920s, 'montage' was a method of juxtaposing shots to derive new meaning that did not exist in either shot alone. In classical Hollywood cinema, a 'montage sequence' is a short segment in a film in which narrative information is presented in a condensed fashion.

Although film director D.W. Griffith was not part of the origins of montage, he was one of the early proponents of the power of editing - mastering cross-cutting to show the occurrence of parallel action in different locations, and codifying film grammar in other ways as well. Griffith's work was highly regarded by Lev Kuleshov and other Soviet filmmakers, greatly influencing their understanding of editing.

Kuleshov was among the very first to theorise about the relatively young medium of the cinema in the 1920s. For him, the unique essence of the cinema - that which could be duplicated in no other medium - was editing. He argued that editing a film is like constructing a building. Brick-by-brick (shot-by-shot), the building (film) is erected. His often-cited Kuleshov Experiment established that montage can lead the viewer to reach certain conclusions about the action within films. Montage works because viewers infer meaning based on context. Sergei Eisenstein was briefly a student of Kuleshov's, but the two parted ways because they had different ideas of montage. Eisenstein regarded montage as a dialectical means of creating meaning. By contrasting unrelated shots, he tried to provoke associations in the viewer, which were induced by shocks. Nevertheless, Eisenstein did not always perform his own editing, as some of his most important films developed were edited by Esfir Tobak.

A montage sequence consists of a series of short shots that are edited into a sequence to condense narrative. It is usually used to advance the story as a whole (often to suggest the passage of time), rather than to create symbolic meaning. In many cases, a song plays in the background to enhance the mood or reinforce the message being conveyed. One famous example of a montage sequence was seen in the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, depicting the start of man's first development from apes to humans. Another example that is employed in many films is the sports montage. The sports montage shows the star athlete training over a period of time, each shot having more improvement than the last. Classic examples of this include Rocky (1976) and The Karate Kid (1984).

Continuity is a term for the consistency of on-screen elements over the course of a scene or film, such as whether an actor's costume remains the same from one scene to the next, or whether a glass holds the same amount of liquid if not drunk throughout the scene. Since films are typically shot out of sequence, the script supervisor will keep a record of continuity, and provide that to the film editor for reference. The editor may try to maintain continuity of elements, or may intentionally create a discontinuous sequence for stylistic or narrative effect.

The technique of continuity editing, part of the classical Hollywood style, was developed by early European and American directors - in particular, D.W. Griffith in his films such as The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916). The classical style embraces temporal and spatial continuity as a way of advancing the narrative, using such techniques as the 180-degree rule, establishing shot, and shot reverse shot. Often, continuity editing entails finding a balance between literal continuity and perceived continuity. For instance, editors may condense action across cuts in a non-distracting way. A character walking from one place to another may 'skip' a section of floor from one side of a cut to the other, but the cut is constructed to appear continuous so as not to distract the viewer.

Early Russian filmmakers such as Lev Kuleshov further explored and theorised about editing and its ideological nature. Sergei Eisenstein developed a system of editing that was designed to be unconcerned with the overall rules of the continuity system of classical Hollywood that he called Intellectual montage.

Alternatives to traditional editing were also explored by early surrealist and Dada filmmakers such as Luis Buñuel (director of 1929's Un Chien Andalou) and René Clair (director of 1924's Entr'acte, which starred famous Dada artists Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray).

The French New Wave filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, as well as their American counterparts such as Andy Warhol and John Cassavetes also pushed the limits of continuity editing during the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s. French New Wave films and the non-narrative films of the 1960s used a carefree editing style, and did not conform to the traditional editing etiquette of Hollywood films. Just like its Dada and surrealist predecessors, French New Wave editing often drew attention to itself by its lack of continuity, its demystifying nature (often reminding the audience that they were watching a film), and its overt use of jump cuts or the insertion of material not often related to any narrative. Three of the most influential editors of French New Wave films were the women who (in combination) edited 15 of Godard's films. These were Françoise Collin, Agnès Guillemot, and Cécile Decugis.

Monday, April 13, 2020

DNA Application Promotional Video Planning

Upon meeting my client, full detail of DNA's purpose was provided, as well as the extent to which it could be utilised. I was given evidence based on tests suggesting that the application would allow collaboration across the world in a shared, global family tree network, enabling relatives to share information with each other. This would ultimately allow users to more easily associate with their current family members, learn about deceased ancestors that existed centuries ago, and appreciate their heritage much more than before. I was also provided with the message that the client wanted me to implement into the advertisement, which was the concept of family. Specifically, it was most important that I make the audience realise the true beauty and significance of the forming and maintenance of bonds between current family members, as well as of the momentous experience of learning about the lives of past relatives. After discussing the application's purpose and message to the world, the client clearly explained the type of audience that my promotion should aim to appeal towards. Consisting of explorers and seekers of their family history, generally between the ages of twenty and eighty, the audience would be the most important aspect of the service. In terms of brand perception, the client obviously requested that the title of the application be present at some point in the video, in addition to the company name and logo being clearly visible at the end of the advertisement. Additionally, the promotion must plainly state that the application is completely free to use, thereby including the downloading, creating of accounts, and receiving of results. Furthermore, although not entirely necessary, it was suggested that I try to include within the visuals a certain shade of crimson that the company is hoping to make people associate with the application, as it is the main colour of the logo, and is used all throughout the program itself.

Due to being told of the application's high potential of enabling users to learn about past relatives that existed many centuries ago, I wanted my advertisement to capture the visual distinctions of previous time periods, along with the fascination that comes from discovering that one's ancestors can be traced back to such periods. Overall, I knew from the beginning that one of the most appropriate ways of promoting this feature was for my advertisement to feature realistic depictions of individuals from certain eras. Such eras would be portrayed through the clothing, makeup, and possessions of each character. This meant that the advertisement would consist of actors using their appearance to represent one of multiple time periods that had yet to be chosen. I performed basic research on the majority of previous eras set after a certain period that Fruit Bowl Tech told me was too unlikely to trace family trees back to. Afterwards, I narrowed the amount that I would include in my advertisement down to ten, based on general appearance. Once I had a general concept in mind, I produced a basic mood board consisting of online images, to help visualise the characters.

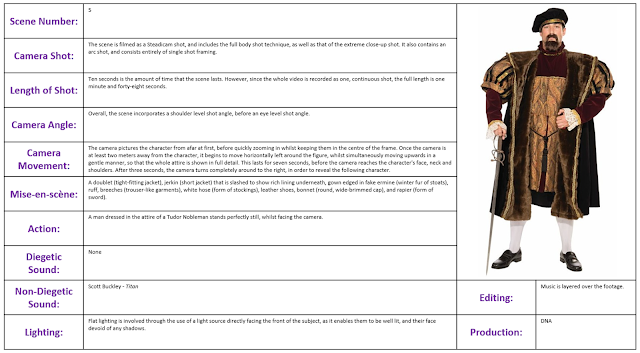

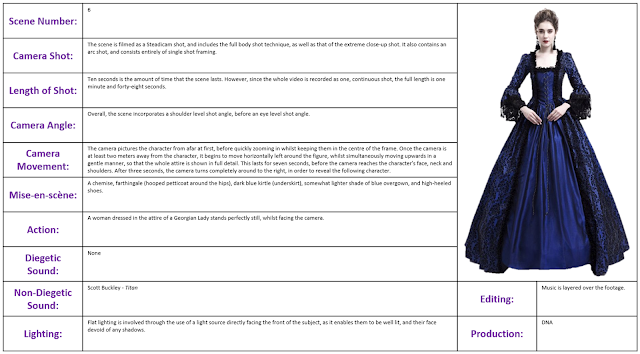

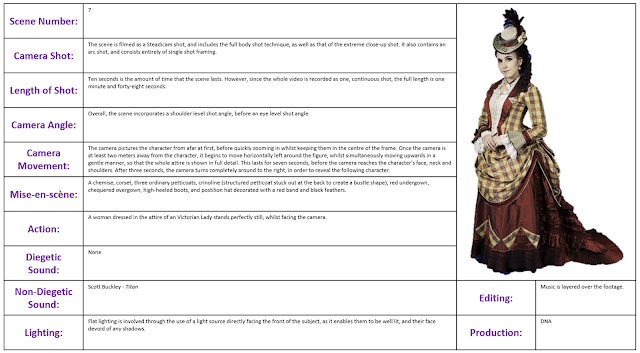

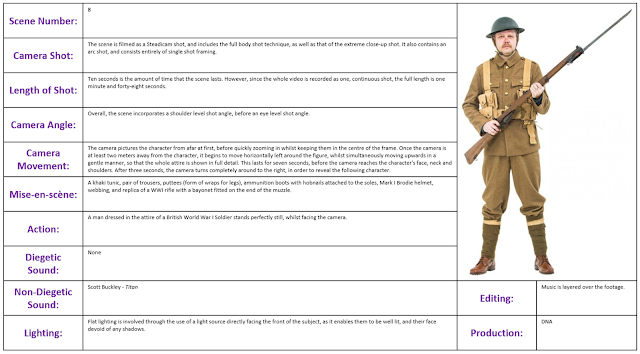

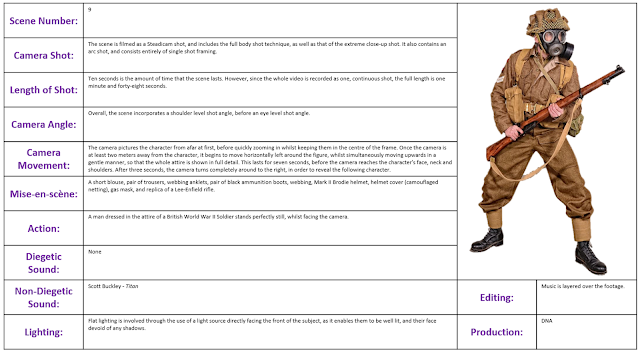

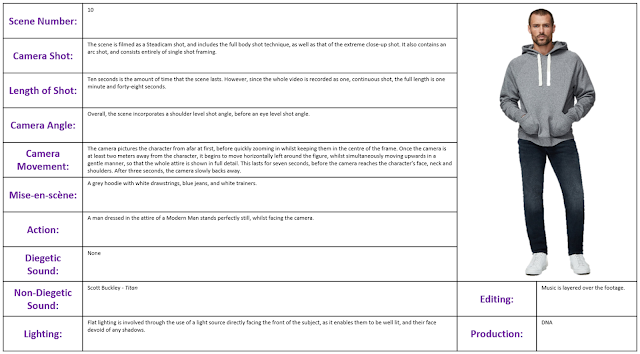

The types of individuals that I had chosen were Ancient Greek, Roman Soldier, Viking Warrior, Renaissance Lady, Tudor Nobleman, Georgian Lady, Victorian Lady, British World War I Soldier, British World War II Soldier, and Modern Man. Satisfied with the idea, I began work on the official planning by creating a storyboard to determine the exact content of the advertisement.

The advertisement would begin by fully presenting the first character: a male civilian from Ancient Greece, dressed in a white chiton (form of tunic) worn underneath a red himation (form of wrap), complete with a pair of leather sandals. Appearing from afar at first, the camera will quickly zoom in, keeping the character in the centre of the frame. Once the camera is at least two meters away from the character, it will begin to move horizontally left around the figure, whilst simultaneously moving upwards in a gentle manner, so that the whole attire is shown in full detail. This will last for seven seconds, before the camera reaches the character's face, neck and shoulders. Their eyes, which will be looking at the camera lens since the beginning of the advertisement, are the main focal point at this time, due to being centered in the frame. After three seconds, the camera will turn completely around to the right, in order to reveal the second character, who will be stood the same distance away as the Ancient Greek originally was.

Stood in place as the new figure, he will be donned in Roman Solider uniform, consisting of a galea (form of helmet), chest armour made of metal strips worn above a red tunic, and caligae (heavy-soled, hobnailed, military sandal boots). He will be wielding a gladius (sword) in his right hand, and a scutum (shield) in his left. The camera shall move in the exact same manner, before turning around to reveal the third character.

As a Viking Warrior, the new individual shall be wearing a brown sort of coat made from faux fur (to represent a real animal pelt), topped with a tunic made of linen, above a pair of woollen trousers and leather boots. The character will also be featured sporting a spangenhelm (form of helmet), and shall be holding a bearded axe in his right hand, as well as a round shield in his left. Once the camera has finished presenting in the same fashion as before, it will turn to exhibit the following historical individual.

In order to capture the likeness of a female civilian from Europe during the period of the Renaissance, the fourth character appears in a chemise (long, white garment resembling a nightdress), underneath a leather corset, mostly covered by a full-length, orange gown. Upon her head sits a conical hennin (form of headdress). The camera will perform its movement, and finish by centering the next character of the advertisement.

For the appearance of a Tudor Nobleman, the next individual will be dressed in a doublet (tight-fitting jacket), topped by a jerkin (short jacket) that is slashed to show rich lining underneath. Worn above this is a gown edged in fake ermine (winter fur of stoats), whilst a ruff is sported around the neck. His legs will be fitted with breeches (trouser-like garments), placed above white hose (form of stockings), accompanied by squared-toed, leather shoes. The top of the head will be covered by a bonnet (round, wide-brimmed cap). To complete the look, the character will be using his right hand to wield a rapier (form of sword). The next individual will be presented through the same use of camerawork.

Following on, the sixth figure - a Georgian Lady - shall be fitted with a chemise, underneath a farthingale (hooped petticoat around the hips) worn to greatly extend and shape the woman's skirts placed over. Atop this will be a dark blue kirtle (underskirt), suited below a somewhat lighter shade of blue overgown, which will be fashioned to allow a front piece of the kirtle to show through in a 'v' shape. Although the skirts will completely cover the figure's legs and feet, she will also wear high-heeled shoes to increase height. Lastly, her hair will be tied back into a loose-fitting bun. Once again, the camera will circle the character to display her thoroughly, before turning to reveal the following figure.

Succeeding the previous individual, the next dresses as a Victorian Lady. Therefore, she will be wearing a chemise, topped with a corset, three ordinary petticoats, and a crinoline (structured petticoat stuck out at the back to create a bustle shape). Above all this, she will sport a red undergown that trails on the floor behind, as well as a chequered overgown that is draped over the front and back of the lady, and ruched up at the sides. Despite her shoes not being seen due to the length of the dress, she will wear high-heeled, leather boots to appear taller. Her hair will be curled, whilst being held high at the back of the head, and pushed over her left shoulder. Atop her head sits a small postilion hat, made with a high crown and narrow brim, decorated with a red band and black feathers. After she has been presented in full detail, the camera will move as it always has done to show the very next individual.

To represent a British World War I Soldier, the following character will be donned in a thick, woolen, khaki uniform consisting of a tunic and a pair of trousers. Many pockets will be sown onto the tunic in specific places, as will a set of brass buttons. Puttees (form of wraps for legs) will be worn around the ankles and calves, above ammunition boots with hobnails attached to the soles. A Mark I Brodie helmet must be placed on his head, and fastened securely using the strap that comes out from either side of the helmet, before being stretched around the chin. He will also wear a webbing for carrying kit around his front, back and shoulders. To finish the look, the character will be using both hands to wield a replica of a WWI rifle with a bayonet fitted on the end of the muzzle. As usual, the camera shall record the soldier, before unveiling the individual that follows.

Being clothed in battledress (form of military uniform adopted by the British Army), the adjacent figure matches the appearance of a British World War II Soldier. The man will sport a short blouse with two pockets, as well as a pair of trousers that features a cargo pocket on the left leg, and is enclosed by webbing anklets. He will also wear a pair of black ammunition boots, along with a webbing for carrying kit around his front, back and shoulders. His head shall be covered by a Mark II Brodie helmet fitted with a chinstrap, and coated with a helmet cover (camouflaged netting). Most of the face will be hidden by a gas mask, and he will will use both hand to hold a replica of a Lee-Enfield rifle. Despite the mask, the camera can still present the character's eyes through the lenses, until it turns to display the next figure.

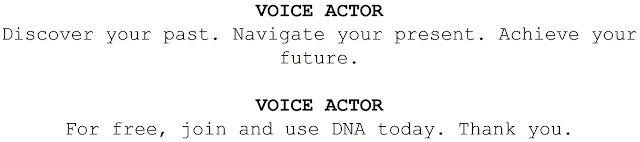

Ending the line of characters, the tenth and final individual will represent a Modern Man by being dressed in a simple, grey hoodie with white drawstrings, combined with blue jeans and white trainers. This modern look will help the majority of target audience viewers to relate to early on in their DNA journey. When the camera has circled the man, and is facing his eyes, instead of turning to the right, it will slowly back away, keeping the character in the centre of the frame. A male voice can be heard calmly saying 'Discover your past. Navigate your present. Achieve your future.'. The visuals will then fade to reveal the application's name and logo, as well as the web address and company phone number, over a background coloured with the shade of crimson used by the service. At this point, the same voice will say 'For free, join and use DNA today. Thank you.', before the advertisement ends. It is important to remember that from the moment that each character appears onscreen, they will not move, remaining frozen in place as if they are statues. Additionally, for the whole runtime, the background used behind and all around the characters will be the same crimson shade that the company hopes people will associate the service with.

For the organised scheduling of tasks, I created a Gantt chart to plan the dates that each duty should be completed by.

A script was required to give to the voice actor that would later be hired, and so I took the time to produce one.

Since the advertisement is to contain no diegetic sound, music is required to suit the visuals. Without any, the video would play in complete silence until the voice-over plays at the end, making the experience seem uninviting and improper. Therefore, in order for the advertisement to be even more enjoyable as well as impactful, I chose to layer the footage with royalty-free, public domain music in the form of Scott Buckley's Titan: a song that both matches and enhances the monumental experience of discovering past relatives and the periods of which they lived in.

For legal reasons, I printed copies of an official form detailing release of the video itself, to later ensure that all actors hired to star in the video would willingly sign.